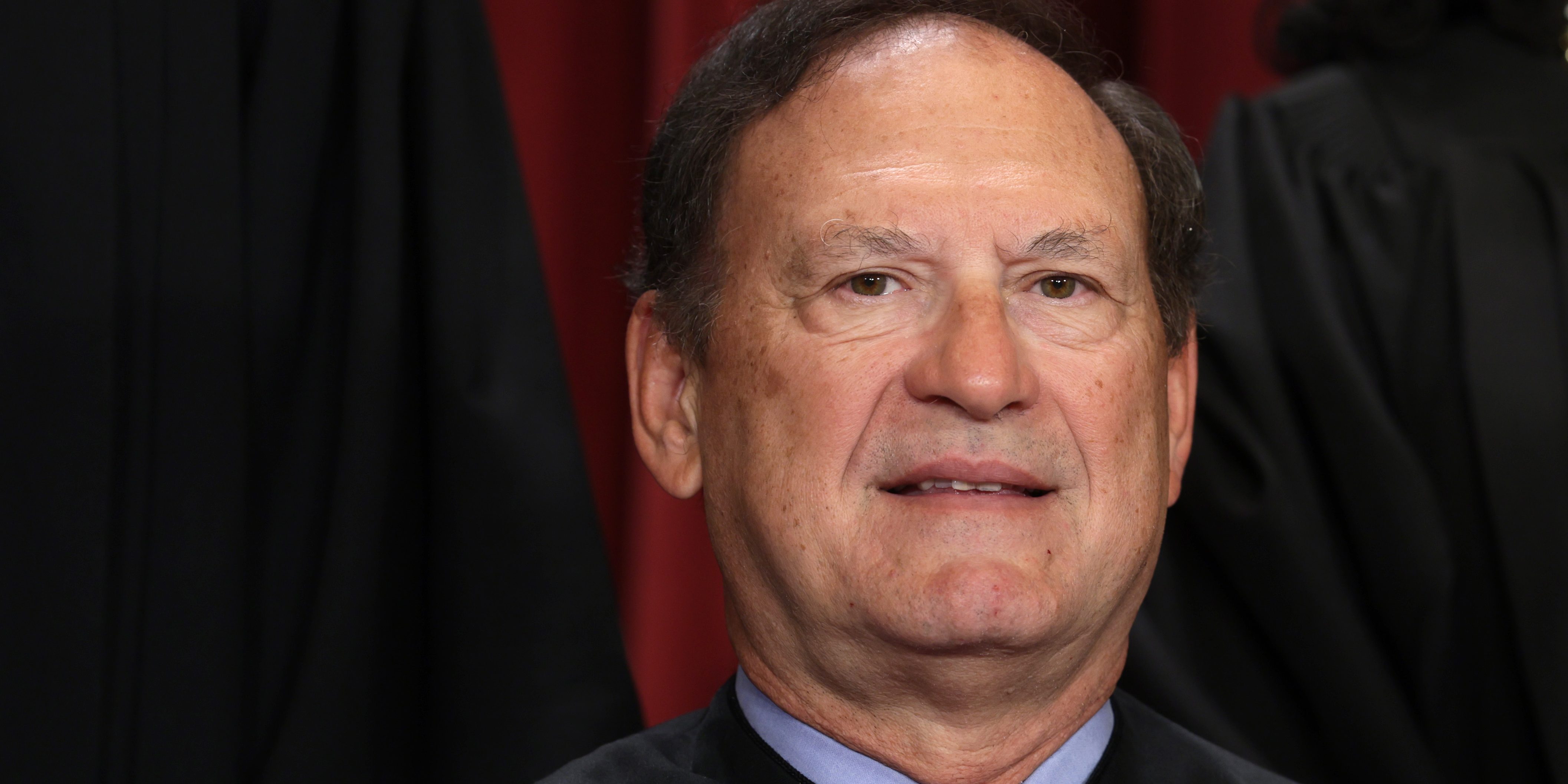

A year ago this month, Martha Ann Bomgardner Alito decided to see if a 160-acre plot of land in Grady County, Oklahoma, would produce. In a lease filed with the Grady County clerk, the wife of Supreme Court Justice Samuel Alito entered into an agreement with Citizen Energy III for revenue generated from oil and gas obtained from a plot of hard scrabble she inherited from her late father. It is one of thousands of oil and gas leases across Oklahoma, one of the top producers of fossil fuels in the United States.

Last year, before the lease was activated, a line in Alito’s financial disclosures labeled “mineral interests” was valued between $100,001 and $250,000. If extraction on the plot proves fruitful, the lease dictates that Citizen Energy will pay Alito’s wife 3/16ths of all the money it makes from oil and gas sales.

In the past, Alito has often recused himself from cases that pose potential conflicts of interest with his vast investment portfolio. Many of these recusals were born from an inheritance of stocks after the death of Alito’s father-in-law, Bobby Gene Bomgardner. Because Citizen Energy III isn’t implicated in any cases before the Supreme Court, Alito’s holding in Oklahoma doesn’t appear to pose any direct conflicts of interest. But it does add context to a political outlook that has alarmed environmentalists since Alito’s confirmation hearing in 2006 — and cast recent decisions that embolden the oil and gas industry in a damning light.

“There need not be a specific case involving the drilling rights associated with a specific plot of land for Alito to understand what outcomes in environmental cases would buttress his family’s net wealth,” Jeff Hauser, founder and director of the Revolving Door Project, told The Intercept. “Alito does not have to come across like a drunken Paul Thomas Anderson character gleefully confessing to drinking our collective milkshakes in order to be a real life, run-of-the-mill political villain.”

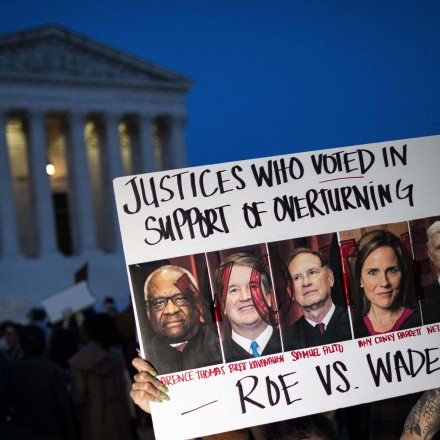

In May, Alito penned a majority decision in Sackett v. EPA which radically scaled back the Clean Water Act, reducing its mandate by tens of millions of acres. According to a statement released by President Joe Biden, the ruling “puts our nation’s wetlands — and the rivers, streams, lakes and ponds connected to them — at risk of pollution and destruction, jeopardizing the sources of clean water that millions of American families, farmers and businesses rely on.” The plaintiffs’ position in the case was backed by the American Gas Association, the American Petroleum Institute, and the Liquid Energy Pipeline Association.

Prior to targeting the Clean Water Act, Alito joined the courts’ other conservative justices in attacking another set of EPA powers under the Clean Air Act in West Virginia v. EPA. The 2022 ruling gutted the EPA’s ability to regulate greenhouse gas emissions from power plants.

A spokesperson for Alito did not respond to The Intercept’s request for comment.

Since his appointment in 2006, Alito has operated as a judicial firebrand, making high-profile appearances at Federalist Society events to excoriate liberal doctrine. He drafted the historic opinion that overturned Roe v. Wade, lashing out in public after the decision was leaked early to the press.

Unlike other federal courts, the Supreme Court does not have a legally binding ethics code. While justices are required to file financial disclosures under the Ethics in Government Act, the choice of whether or not to recuse from cases involving a conflict of interest is entirely self-enforced.

This loophole caught the public’s attention in April, when a ProPublica report detailed the lavish, undisclosed gifts and financial support Justice Clarence Thomas and his family received from billionaire GOP megadonor Harlan Crow. Since then, other justices’ financial dealings have been called into question, including Neil Gorsuch for an undisclosed property sale to a lawyer with business before the court, and John Roberts, whose wife’s employment as a legal recruiter for Supreme Court-bound lawyers raised a host of ethics questions.

Alito now finds himself in a position similar to Thomas, after another ProPublica report from last week described a fishing trip and private jet ride the justice took with conservative operative Leonard Leo and billionaire hedge fund manager Paul Singer, valued at over $100,000. While pictures from the trip suggest that Alito personally appreciates the bounty of America’s dwindling unpolluted landscape, his rulings in environmental cases suggest that politically he does not.

Before publishing its investigation into Alito’s relationship with Singer — whose business model is organized around using the courts, including the Supreme Court, to extract payments from distressed bond issuers — ProPublica reached out to Alito with a list of questions. Alito responded by penning a defensive essay in the Wall Street Journal, which published the response before ProPublica had even published its story.

“What makes political figures who violate ethics laws so exceptional is how much obviously unethical behavior is legal under our current overly permissive rules,” Hauser said. “Our current ethics regime assumes that a person’s financial interests need to be extremely specific in order to influence their behavior, a worldview that ignores the foresight rich people and corporations regularly demonstrate.”

Prior to the lease, Alito ruled on cases with the potential to impact gas and oil prices, both nationally and in Oklahoma. In Oneok, Inc. v. Learjet, Inc., decided in 2015, Alito ruled with the majority to head off an attempt to block state antitrust laws from being applied to natural gas companies under the Natural Gas Act. Oneok, the largest supplier of natural gas in Oklahoma, runs an active natural gas pipeline through the Alito plot.

In 2017, Alito delivered an address at the Claremont Institute, a conservative think tank, that further clarified his position on fossil fuels’ role in climate change. “Carbon dioxide is not a pollutant. Carbon dioxide is not harmful to ordinary things, to human beings, or to animals, or to plants.” Alito said. “It’s actually needed for plant growth. All of us are exhaling carbon dioxide right now. So, if it’s a pollutant, we’re all polluting.”

In 2021, Alito joined the majority in PennEast Pipeline Co. v. New Jersey to protect the right for companies with federal backing to exercise eminent domain in the seizure of state property. PennEast Pipeline, a natural gas distributor, sought to maintain its ability to seize land in the construction of a pipeline, and thanks to the Supreme Court ruling, it was able to preserve a tactic for pipeline construction, which, if overturned, would have significantly impacted the ability for the natural gas industry to expand pipelines and production.

Over the past two years, Citizen Energy has launched a buying spree of wells and land rights, positioning itself as one of the top private producers in Oklahoma. It operates over 200 miles of natural gas-gathering pipelines and over 700 wells, and produces over 80,000 barrels of oil equivalent per day. It is financially backed by the private equity behemoth Warburg Pincus.